Știri

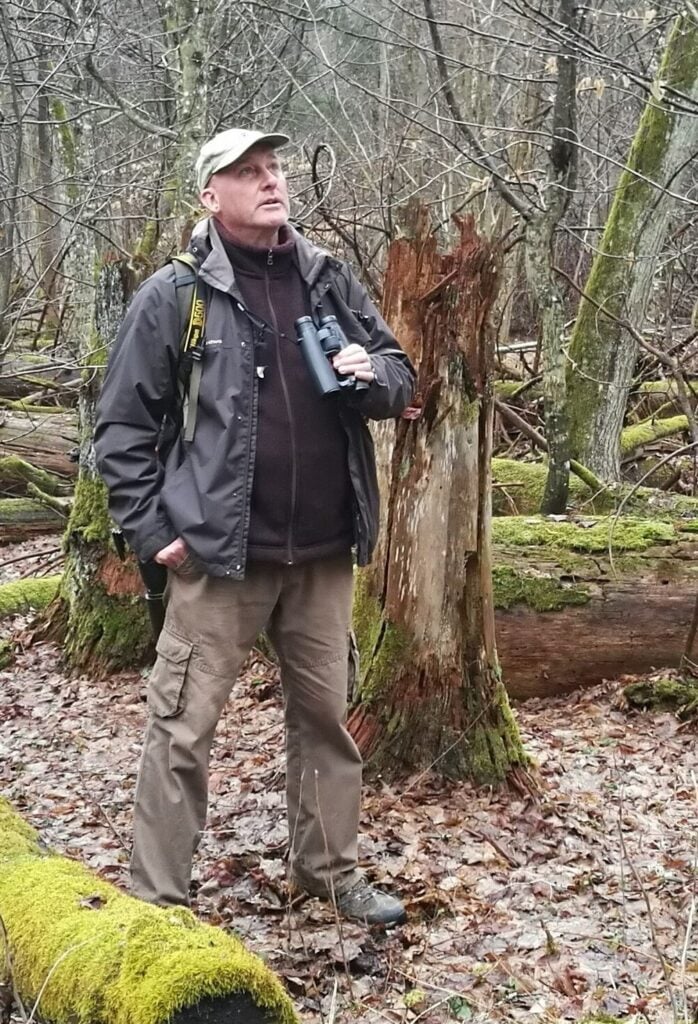

Membri expați. Gerard Gorman, cunoscutul specialist în ciocănitori

12 aprilie 2024

Pentru păsărarii iubitori de ciocănitori Gerard Gorman e probabil primul nume care le vine în minte, nume pe care te aștepți să îl vezi scris pe cărți și în articole de specialitate. Mai puțin în arhiva Membrilor SOR, în paginile Buletinului de Informare nr. 1 din 1992.

Teodora Domșa: Comunitatea noastră, dar și cei care ne urmăresc, vă știu drept un apreciat ornitolog, specialist al ciocanitorilor. Dar suntem convinși că vor fi surprinși să afle, ca mine de altfel, că ați fost printre primii membri SOR, posesor al cardului de membru cu numărul 192. Răsfoind vechi documente, v-am descoperit numele într-unul dintre primele buletine de informare ale SOR, editate de Peter Weber și Mitruly Aniko. Cum s-a întâmplat acest lucru?

Gerard Gorman: La finalul anilor ’80, începutul anilor ’90 eram stabilit în Ungaria, în Budapesta mai exact, și călătoream adesea în România, prin Transilvania, dar și prin Delta Dunării și Dobrogea. M-am împrietenit cu câțiva amici păsărari, printre care Peter, Aniko și Dan Munteanu. Sunt mândru dacă am fost primul membru străin al SOR!

TD: Știm că imediat după căderea comunismului organizațiile ornitologice proaspăt înființate din țările fost comuniste au beneficiat de suportul oferit de colegii din vest, în special de către Societatea Regală pentru Protecția Păsărilor (RSPB). Fie că a fost vorba de transfer de cunoștințe – traininguri, de ajutor financiar sau logistic (echipamente), pentru multe dintre aceste organizații a reprezentat supraviețuirea în anii tulburi ai tranziției. Ați fost parte din acest efort?

GG: Da, am condus de câteva ori către Cluj (locul primului birou SOR) cu mașina plină pentru SOR. În una dintre ocazii am dus o mașină de fotocopiat!

TD: Ce presupunea statutul de membru „internațional” în afară de achitarea cotizației? Ce perioadă ați fost membru cotizant al SOR?

GG: Nu îmi aduc aminte cu precizie, dar cred că era o cotizație de membru mică. Din păcate, mi-am întrerupt de ceva vreme susținerea ca membru a SOR.

TD: Cum au fost interacțiunile cu ornitologii și pasionații de păsări din România? Știu că ați cunoscut zona Balcanilor încă dinainte de căderea comunismului. Erați încă de atunci în contact cu ei?

GG: Din păcate Peter Weber și Dan Munteanu nu mai sunt printre noi, iar eu am pierdut contactul cu alți membri fondatori ai SOR. Timpul a zburat. Atât de multe lucruri s-au schimbat între timp. Nu mai sunt în contact cu noua generație de ornitologi din SOR.

TD: Ați străbătut ca ghid țările dintre Marea Baltică și Marea Neagră înainte de 1990. Cum se prezenta biodiversitatea acestor țări atunci și cum vi se pare acum, după mai bine de trei decenii? Ați scris o carte, „Păsările și schimbările politice din Europa de Est”, în care vorbiți despre efectele schimbărilor survenite o dată cu căderea comunismului asupra naturii. Din vasta dumneavoastră experiență, dobândită în atâtea zeci de ani în care ați străbătut mare parte din lume, puteți spune că există un sistem politic sau economic mai blând cu natura? Puteam alege o cale mai bună după 1990?

GG: De fapt, „Păsările și schimbările politice din Europa de Est” nu este o carte, ci un articol scris pentru un ziar din SUA. Sunt bune întrebările, dar nu au răspunsuri ușoare. De unde să încep? Privirea retrospectivă poate fi ceva comod, confortabil. Nu sunt eu cel în măsură să spun dacă SOR trebuia să urmeze o cale mai bună. Dar, per ansamblu, cred că SOR, și alte asemenea organizații din zonă, au făcut o treabă grozavă, adesea în circumstanțe dificile.

TD: Fiind în strâns contact și lucrând în domeniul protecției mediului și al păsărilor, atât în statele vestice și în cele din estul Europei, dar și pe alte continente, credeți că ONG-urile pot influența semnificativ deciziile favorabile naturii și biodiversității? Care ar fi super puterea lor și a membrilor afiliați? Aveți un sfat pentru membrii SOR?

GG: ONG-urile care activează în domeniul conservării trebuie adesea să țină piept unor oponenți puternici. Guverne care nu susțin cauza naturii și un lobby puternic din partea mediului de afaceri, al agricultorilor, al vânătorilor și silvicultorilor. Asta peste tot în lume. Sfatul meu este să continuați, să faceți lucruri în continuare. Lucrați cu oameni care gândesc ca voi și implicați cadre didactice, copii, elevi și studenți. Poate părea evident, dar e nevoie de repetiție.

TD: Și acum să vorbim mai mult despre păsări! De ce ciocănitori? Ce anume le-a impus în fața altor specii în preferințele dumneavoastră? Au fost pe primul loc încă de cînd erați un juvenil în ale ornitologiei sau v-au cucerit treptat?

GG: De ce ciocănitori? Am fost întrebat acest lucru de atât de multe ori! Dar adevărul este că nu știu exact de ce. Pot spune însă că întotdeauna am preferat o plimbare prin pădure mai mult decât în orice alt habitat. Și care păsări sunt mai intrinsec legate de păduri, de arbori? Încă un motiv a fost faptul că am crescut în Anglia, unde sunt doar trei specii de ciocănitori care cuibăresc, și când am început să călătoresc prin centrul și estul Europei am observat repede că acolo pot fi până la 10 specii! De asemenea, am fost influențat și de rolul de specii cheie sau specii umbrelă pe care ciocănitorile îl au în ecosistemele forestiere și în comunitățile păsărilor.

TD: Aminteam de turneul din țările balcanice înainte și la începutul anilor ’90. De ce ați ales să vă stabiliți în Ungaria, nu neapărat cea mai darnică în ceea ce privește diversitatea speciilor de ciocănitori și a habitatelor forestiere?

GG: Eram în căutarea unei burse în această regiune și singura care era disponibilă era în Ungaria. De fapt, deși Ungaria nu are pădurile pe care le întâlnim în unele zone din Transilvania, are habitate bune pentru ciocănitori. În Europa sunt unsprezece specii de ciocănitori, iar Ungaria este casă pentru nouă dintre ele, având doar cu una mai puține specii decât România.

TD: Câte specii de ciocănitori mai sunt încă în lume? Care continent stă cel mai bine ca număr și care se poate lăuda cu cele mai spectaculoase specii?

GG: La nivel global sunt în jur de 240-250 de specii. Cea mai mare diversitate de specii de ciocănitori este în America Centrală, America de Sud și sud-estul Asiei. Familia ciocănitorilor e diversă, unele sunt mici, altele mari, unele colorate, altele mai degrabă modeste ca penaj. Unele specii sunt comune, altele sunt serios amenințate. Atât de multe dintre ele sunt de-a dreptul spectaculoase, încât realmente nu pot alege una.

TD: După atâtea decenii dedicate acestor carismatice păsări aveți, mă gândesc, și o specie favorită. Care ciocănitoare a reușit să vă fascineze și să vă câștige admirația?

GG: Cum spuneam, sunt prea multe ca să le pot enumera, îmi pare rău. Dar pot menționa una care mă fascinează, una pe care nu am reușit să o văd! Ciocănitoarea de Okinawa (Dendrocopos noguchii) care se găsește doar în insula japoneză Okinawa. E rară, amenințată și frumoasă. Trebuie să ajung acolo!

TD: Povestiți-ne una din experiențele dumneavoastră din România legată de speciile de ciocănitori de aici.

GG: În anii ’80, când am vizitat pentru prima dată Delta Dunării, am fost surprins de numărul mare de specii de ciocănitori de acolo. Sigur, Delta este o zonă umedă uriașă, fantastică, iar păsările acvatice nu m-au dezamăgit, dar am fost încântat să văd atât de multe ciocănitori.

TD: Știu că nu doar observați păsările, ci le înregistrați și sunetele. În cazul ciocănitorilor ce vă spune mai mult despre aceste păsări, cântecul sau darabana?

GG: Categoric da, darabanele diferitelor specii de ciocănitori sunt definitorii.

TD: SOR tocmai a lansat ca schemă voluntară programul de monitorizare a ciocănitorilor. Ce informații esențiale și sfaturi de bună practică ați putea oferi colegilor și voluntarilor noștri?

GG: Excelent! E foarte important să alegi metoda de monitorizare potrivită. Dar în același timp, una care să fie destul de simplă, una pe care nu doar experții, ci toți participanții, să o poată aplica.

TD: Luând în considerare ultimele informații privind tendințele populaționale ale speciilor de ciocănitori în conexiune cu managementul forestier în Europa, cum vedeți viitorul acestui grup pe continentul nostru?

GG: După cum prea bine știți și voi, cei de la SOR, în multe zone habitatele forestiere s-au degradat sau chiar au dispărut. Din păcate, practicile forestiere actuale sunt arareori favorabile.

TD: La final am dori să aflăm dacă plănuiți să vă reîntoarceți în România în viitorul apropiat, fie ca cercetător, fie ca birdwatcher.

GG: În prezent, mă strădui să ajung în România o dată pe an. Nu am mai fost de ceva vreme în munți, așa că ar trebui să ajung acolo cât de repede. Până atunci, vă doresc celor de la SOR toate cele bune. Continuați să faceți lucrurile bune și importante pe care le-ați făcut și până acum!

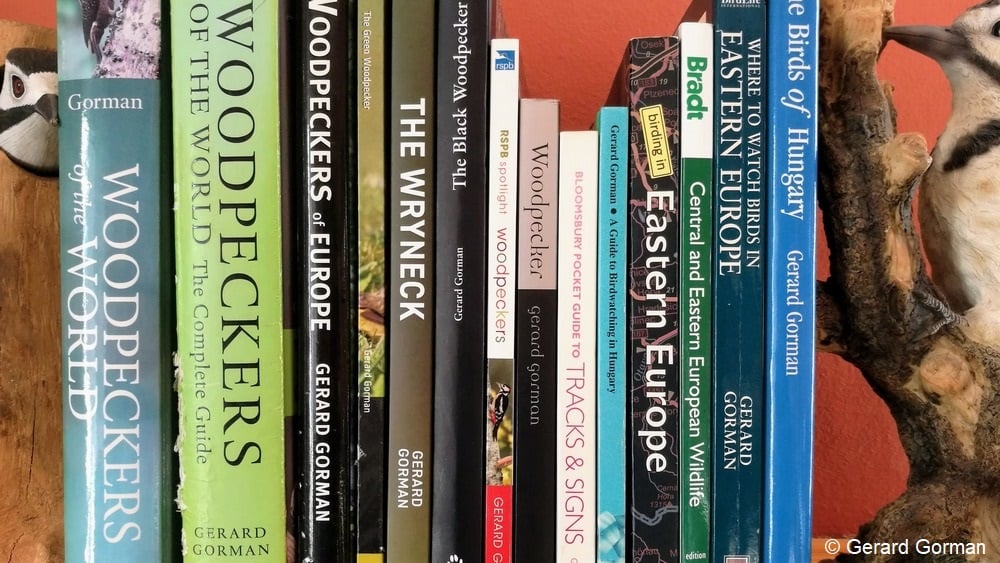

Gerard Gorman este autorul cărților:

The Green Woodpecker (Pelagic Publishing)

The Wryneck (Pelagic Publishing)

Woodpeckers of the World (Helm-Bloomsbury)

Woodpeckers of Europe (Bruce Coleman)

The Black Woodpecker (Lynx)

Woodpecker (Reaktion)

Woodpeckers (RSPB/Bloomsbury)

Aici puteți citi varianta în engleză a articolului

For avid woodpecker enthusiasts, Gerard Gorman is probably the first name that comes to mind, a name you expect to see written on books and in specialist articles. Less in the archive of SOR Members and on the pages of the Information Bulletin no. 1 of 1992.

Teodora Domșa: Our community, as well as those who follow us, know you as an acclaimed ornithologist, a woodpecker specialist. But we are convinced that they are also amazed to learn, as I am, that you were among the first SOR members, holder of membership card number 192. Looking through old documents, I discovered your name in one of the first newsletters of SOR, edited by Peter Weber and Mitruly Anikó. How was this possible?

Gerard Gorman: I was based in Budapest, Hungary, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, and often travelled into Romania, around Translvania and also to the Danube Delta and Dobrugea. I made friends with a few fellow birders, includer Peter, Anikó and Dan Munteanu. If I was the first foreigner to be a SOR member then I am proubd of that.

TD: We know that, immediately after the fall of communism, the newly established ornithological organizations in ex-communist countries benefited from the support offered by their western colleagues, in particular by The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB). Whether it was knowledge transfer, in the form of training, financial aid or logistics (equipment), for many of these organizations this helping hand assured their survival in the turbulent years of transition. Were you part of this effort?

GG: Yes, I drove to Cluj a few times with staff from the RSPB. On one occasion we brought a photcopying machine!

TD: What did “international” membership entail, besides paying a membership fee? How long have you been a paying and active member of SOR?

GG: I can’t remember exactly, but I think there was a very small membership fee. Unfortunately, I have lapsed as a member.

TD: How did you interact with ornithologists and bird enthusiasts from Romania? I know you have known the Balkans since before the fall of communism. Have you been in contact with them since those times?

GG: Sadly, Peter Weber and Dan Munteanu have passed away, and I have lost contact with some of the other founder members of the SOR. Time has flown. So many things have changed. I am not really in contact with the new younger generation of SOR.

TD: You traveled as a guide through the countries between the Baltic and the Black Sea before 1990. What was the state of biodiversity in these countries then and how does it seem to you now, after more than three decades? You wrote a book, “Birds and Political Change in Eastern Europe”, in which you talk about the effects that the changes that came with the fall of communism had on nature. From your vast experience, acquired in so many years during which you have “walked” much of the Earth, can you say that there is a political or economic system that is kinder to nature? Could we have chosen a better path after 1990?

GG: Actually, “Birds and Political Change in Eastern Europe” was an article for a USA magazine, not a book. Those questions are good ones, but not easy to answer. Where should I begin? Retrospect can be a convenient thing. It is not for me to say now whether the SOR should have taken ”a better path”. But overall I think that the SOR, and other organisations in the region, have done great work, often in difficult circumstances.

TD: Being in close contact and working in the field of birds and environmental protection, both in Western and Eastern European states, and also in other continents, do you think that NGOs can significantly influence decisions favorable to nature and biodiversity? What would be the superpower of NGOs and their affiliate members? Do you have a piece of advice for SOR members?

GG: Conservation NGOs often have to face powerful opponents. Unsympathetic governments and strong business, farming, hunting and forestry lobbies. All over the world. My advice is just to keep going, keep doing things. Work with like-minded people and involve teachers, kids and students. That may all seem obvious, but it needs repeating.

TD: And now let’s talk more about birds! Why woodpeckers? What exactly sets them above other species in your preferences? Have they been in the pole position since you were a juvenile ornithologist or did they win you over gradually?

GG: Why woodpeckers? I have been asked that many, many times. The truth is, I do not know why. I can say that, ultimately, I have always preferred a walk in a forest over a walk around other habitats. And which birds are inextricably connected to forests, to trees? Another thing was that I was brought up in England, where there are only three breeding woodpeckers, and when I started to travel around central and eastern Europe I soon saw that there could be up to ten! The role that woodpeckers play in forest ecosystems and bird communities as „keystone species” and „umbrella species” influenced me, too.

TD: I mentioned earlier your tour in the Balkan countries, before and in the early 90s. Why did you choose to settle in Hungary, a country not necessarily the most generous in terms of woodpecker diversity and forest habitats?

GG: I was looking for a scholarship to this region and the only one available was to Hungary. Actually, although Hungary does not have forests quite like some of those in Transylvania, there are good woodpecker habitats. There are eleven woodpecker species in Europe and Hungary is home to nine of them, that is only one behind Romania.

TD: How many species of woodpeckers are there still in the world? Which continent stands the best in numbers and which boasts the most spectacular species?

GG: There are around 240-250 species globally. The „hotspots” for woodpecker diversity are Central and South America and south-east Asia. The family is diverse, some are tiny, some big, some are colourful, others rather plain. Some are common, others are seriously threatened. There are so many spectacular ones, that I can’t really choose one.

TD: After so many decades dedicated to these charismatic birds you have, one might think, a favorite species. Which woodpecker managed to fascinate you and win your admiration?

GG: As I said, there are too many to mention, sorry. But I can mention one that fascinates me, one that I have not seen! The Okinawa Woodpecker (Dendrocopos noguchii) which is found only on the Japanese island of Okinawa. It is rare, endanerted and beautiful. I have to get there.

TD: Tell us one of your Romanian experiences related to the local species of woodpeckers.

GG: When I first went to the Danube Delta, in the 1980s, I was surprised at how many woodpeckers there were. Of course, it is a huge, fantastic wetland, and the waterbirds did not disappoint me, but I was delighted to see so may woodpeckers there.

TD: I know you are not just a birdwatcher, but also a keen bird sound recordist. In the case of woodpeckers, do the drummings or the calls tell you more about these birds?

GG: Absolutely, yes, the drummings of the different woodpecker species are diagnostic.

TD: SOR has just launched the Woodpecker Monitoring Program as a voluntary scheme. What insight and good practice advice can you give to our colleagues and volunteers?

GG: Excellent! It will be important to choose the right surveying method. But also one that is fairly simple, one that everyone, not just „experts” can use.

TD: Taking into account the latest information on population trends of woodpecker species in connection with forest management in Europe, how do you see the future of this group on our continent?

GG: Well, as the SOR will know, in many areas wooded habitats have been degraded and sometimes even lost. Sadly, today’s forestry management practises are seldom favourable.

TD: Finally, we would like to know if you plan to return to Romania in the near future, as a researcher or for birdwatching.

GG: These days, I try to visit Romania once a year. I have not been to the mountains for a while, so I should try to get back there soon. In the meantime, I wish you and the SOR all the best. Keep up the important and good work!

Gerard Gorman is author of:

The Green Woodpecker (Pelagic Publishing)

The Wryneck (Pelagic Publishing)

Woodpeckers of the World (Helm-Bloomsbury)

Woodpeckers of Europe (Bruce Coleman)

Te Black Woodpecker (Lynx)

Woodpecker (Reaktion)

Woodpeckers (RSPB/Bloomsbury)

Uite barza! – live stream cuib

Arhive

Newsletter

Noutati

Începe al doilea an al Recensământului Internațional al berzelor albe

Societatea Ornitologică Română (SOR), în parteneriat cu Asociația pentru Protecția Păsărilor și a Naturii „Grupul Milvus”, anunță lansarea celei de-a doua etape a Recensământului Internațional al berzelor albe în România, în perioada 10 iunie – 15 iulie.

Proiecte

Euro Bird Portal

EuroBirdPortal (EBP) este o inițiativă a EBCC, un portal care agregă în timp real datele observaționale de păsări din Europa. Proiectul își propune să aducă împreună datele încărcate zilnic în diverse portaluri, de mii de observatori din toate țările europene. În portal pot fi vizualizate datele agregate săptămânal, pentru perioada în curs, dar și datele […]

Sezon reproductiv slab pentru șoimul dunărean în Sudul României: doar trei perechi au cuibărit cu succes

Sezon reproductiv slab pentru șoimul dunărean în Sudul României: doar trei perechi au cuibărit cu succes  Deși puțini în Dobrogea, șoimii dunăreni au devenit foarte cunoscuți printre școlarii din Adamclisi, Horia și Saraiu

Deși puțini în Dobrogea, șoimii dunăreni au devenit foarte cunoscuți printre școlarii din Adamclisi, Horia și Saraiu  Luna mai a adus un nou val de observații și trei câștigători în competiția de Ziua Păsărilor Migratoare

Luna mai a adus un nou val de observații și trei câștigători în competiția de Ziua Păsărilor Migratoare  Privighetorile noastre cu arcuș și sirinx

Privighetorile noastre cu arcuș și sirinx  Noaptea Privighetorilor 2025 – 35 de ani de SOR sărbătoriți și la Cluj

Noaptea Privighetorilor 2025 – 35 de ani de SOR sărbătoriți și la Cluj  În lumea păsărilor penajul contează mai mult decât am crede

În lumea păsărilor penajul contează mai mult decât am crede  15 modele de hoteluri de insecte pentru o grădină prietenoasă cu natura

15 modele de hoteluri de insecte pentru o grădină prietenoasă cu natura  Scorușul de munte

Scorușul de munte  În 27 februarie e sărbătorită Ziua mondială a organizațiilor non-guvernamentale

În 27 februarie e sărbătorită Ziua mondială a organizațiilor non-guvernamentale  Iedera

Iedera  Conservarea gâștelor cu gât roșu

Conservarea gâștelor cu gât roșu  Conservarea șoimului dunărean în NE Bulgariei, Ungaria, România și Slovacia

Conservarea șoimului dunărean în NE Bulgariei, Ungaria, România și Slovacia  Conservarea acvilei țipătoare mici în România

Conservarea acvilei țipătoare mici în România  Investigarea prezenței dropiei în România

Investigarea prezenței dropiei în România  Salvați pelicanul creț în Delta Dunării

Salvați pelicanul creț în Delta Dunării  Uite Barza!

Uite Barza!  Atlasul Păsărilor din București

Atlasul Păsărilor din București  Monitorizarea Păsărilor Comune

Monitorizarea Păsărilor Comune  Protecția berzei albe în Lunca Dunării

Protecția berzei albe în Lunca Dunării  International WaterBird Count

International WaterBird Count  Restoriver

Restoriver  POIM Moldova

POIM Moldova  POIM SUD

POIM SUD  ROSPA0059 Lacul Strachina

ROSPA0059 Lacul Strachina  ROSPA0052 Lacul Beibugeac

ROSPA0052 Lacul Beibugeac  Școli și grădinițe prietenoase cu natura

Școli și grădinițe prietenoase cu natura  Spring Alive

Spring Alive  Pasărea Anului

Pasărea Anului  Euro Bird Portal

Euro Bird Portal  Restore Nature

Restore Nature  România Prinde Aripi

România Prinde Aripi  Aripi Libere

Aripi Libere  Agricultură pentru biodiversitate

Agricultură pentru biodiversitate  Big Day_Maraton ornitologic

Big Day_Maraton ornitologic  It is time!

It is time!  PETlican

PETlican  Noaptea Privighetorilor

Noaptea Privighetorilor  Păsările Clujului

Păsările Clujului  Mic determinator de insecte

Mic determinator de insecte  Păsări din pădure

Păsări din pădure  Mic determinator de fluturi

Mic determinator de fluturi  Mic determinator de plante

Mic determinator de plante  Ce floare este aceasta?

Ce floare este aceasta?  Insignă orhidee albină

Insignă orhidee albină  Insignă șoim dunărean

Insignă șoim dunărean  Insignă lăcustar

Insignă lăcustar  Insignă sfrâncioc roșiatic

Insignă sfrâncioc roșiatic  Insignă râs model 2

Insignă râs model 2  Cascadia: Monumente ale naturii

Cascadia: Monumente ale naturii  Colecția de puzzle-uri educative Păsări acvatice

Colecția de puzzle-uri educative Păsări acvatice  Joc memory Găsește perechea

Joc memory Găsește perechea  Joc memory Păsări comune din parcuri și grădini

Joc memory Păsări comune din parcuri și grădini  Puzzle Păsări care se hrănesc pe malurile apelor

Puzzle Păsări care se hrănesc pe malurile apelor  Sacoșă bujor

Sacoșă bujor  Sacoșă prigorie în zbor

Sacoșă prigorie în zbor  Sacoșă pescăraș albastru

Sacoșă pescăraș albastru  Cuib huhurez mic

Cuib huhurez mic